Could birdwatching save Latin America's forests?

Every time I have traveled in the past ten years it has been to look at birds. I keep a personal list of the birds I've seen so I remember each and every encounter I've had, whether with noisy flocks or solitary individuals. At the end of last December, a group of birding pals and I counted 120 different species of birds over the course of 13 hours in Ecuador's Amazon region.

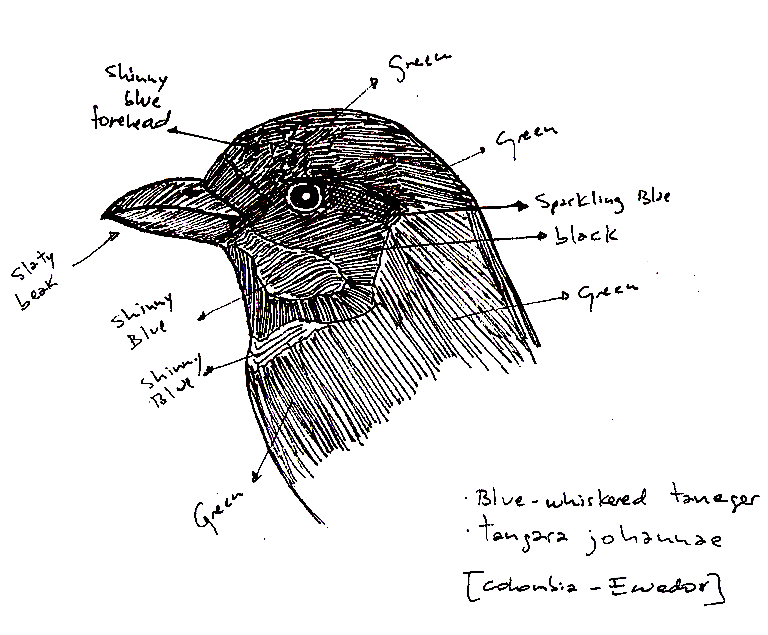

Line drawing by Manuel Sánchez.

The tally was part of the Audubon's Christmas Bird Count in Morona Santiago, Ecuador. In a small patch of secondary forests, open pasture, small plantations and dirt roads, we observed more than 45 percent of the United Kingdom's entire number of bird species. In northern Ecuador, in places like Mindo or Cosanga, people report between four and five hundred different species of birds every year during the same Christmas bird count.

Birding is a hobby—and, at times, an obsession—practiced by millions of people in Europe and United States. Members of this subculture congregate by the thousands during spring festivals in the U.S. to observe and celebrate the return of birds from their wintering grounds in Central and South America. In the U.K., the British Birdwatching Fair in Rutland is held in August and attracts over 20,000 visitors.

This widespread enthusiasm could be seen in Latin America. But why would people travel thousands of miles to observe birds? I'll give you one good reason they should: In the eyes of birdwatchers, Latin America is paradise. More than 3,000 species can be found in the Neotropics.

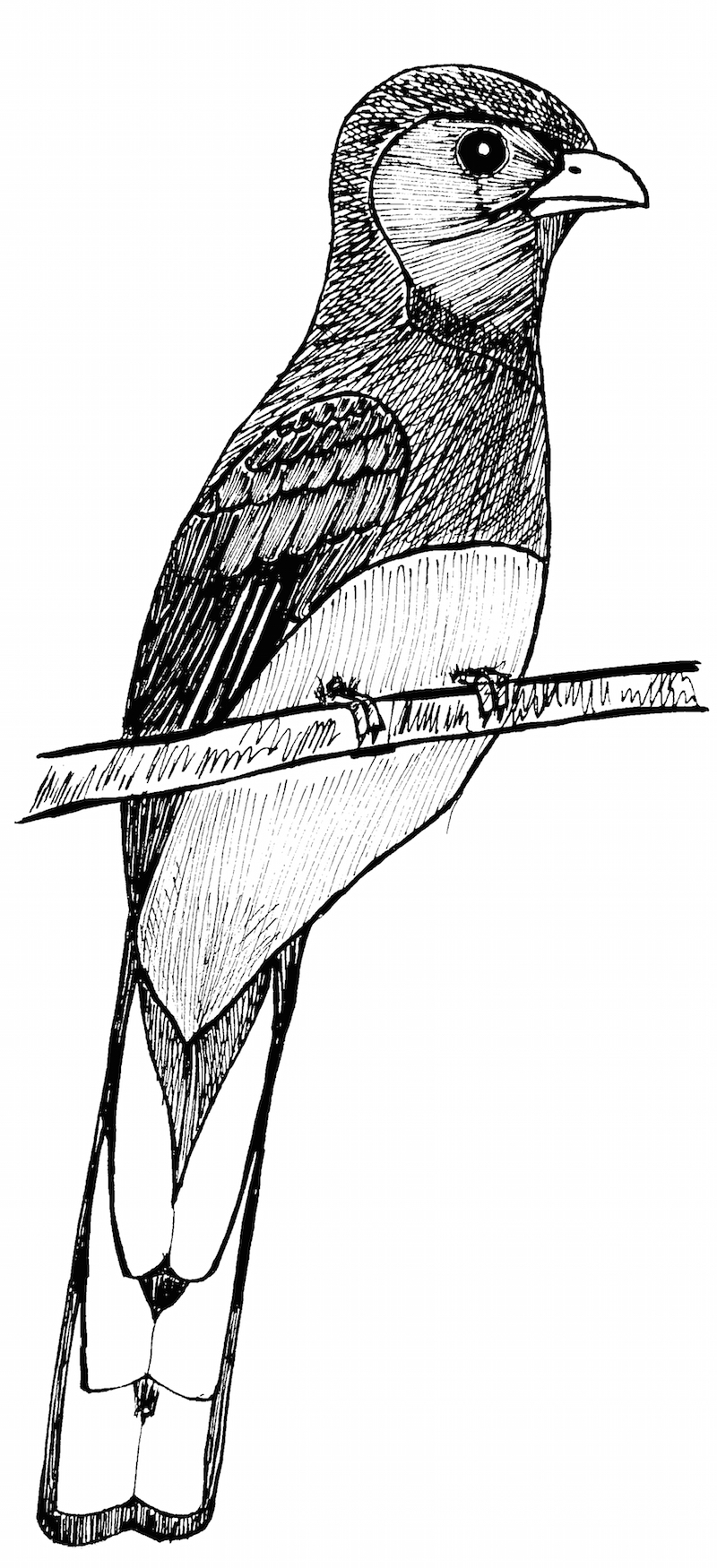

Line drawing by Manuel Sánchez.

Covering most of Latin America, the Neotropics stretch from southern Mexico to Chile, including Florida and the Caribbean. The Neotropics are one of the world's eight ecozones and they host thousands of unique bird species—from the Resplendent Quetzals of southern Mexico to Darwin's finches in Ecuador's Galapagos Islands to the throngs of sea birds along the Patagonian coasts of Argentina.

Bird Life International, a bird conservation organization, has identified more than two hundred Endemic Bird Areas worldwide and more than 35 percent of these are located in the Neotropics. And scientists are still finding more birds there. In 2013, a group of Brazilian and American scientists described 15 new species, 11 of which are endemic to Brazil.

Foreign birdwatchers have been flocking to Latin America to see birds for decades. In 2014, a group of ornithologists from Louisiana State University traveled to Peru and set the world record for the most species observed in one day: 354 species.

'Big days' in Latin America and the Caribbean where over 100 bird species were observed in one day.

Sightings compiled by ABA.org from 1976 to 2014.

Line drawing by Manuel Sánchez.

The benefits are obvious: by establishing birdwatching reserves, huge swathes of forests would ostensibly be protected from extractive industries like mining, logging and drilling. But are Latin Americans interested in looking at birds?

In fact, there's a precedent. Colombia, which hosts the most species of birds in the world, has a National Network of Birdwatchers (Red Nacional de Observadores de Aves) which congregates different organizations related to bird conservation. In Brazil, the wikiaves web group conveys nearly twenty thousand members.

Moreover, the four South American countries with the most species of birds in the world—Colombia (1,835 species), Brazil (1,787 species), Peru (1,771 species), and Ecuador (1,609 species)—have been running annual ornithological congresses, birdwatching fairs, and Christmas bird counts that have been seeing an increase in the number of participants. Some of these nations have been developing strategies to promote birding tourism as a tool for recreation and conservation.

Ecuador recently designated Mashpi–Pachijal in the Chocó Region of northern Ecuador as an 'Important Bird Area' where several endemic and rare birds are found, including the Black Solitaire, the Indigo Flowerpiercer, the Moss–backed Tanager, and the endangered and very rare Chocó Vireo and Banded Ground Cuckoo. In northeast Brazil, a 140–acre reserve was created to protect the critically endangered Araripe Manakin, of which only 800 individuals are thought to remain.

In November 2014, the staff of Un Poco del Chocó Reserve and Research Station in Ecuador alerted the birding world that the Banded Ground Cuckoo had returned to its habitat after fourteen months in which it was thought to have disappeared.

The Banded Ground Cuckoo is one of the most elusive birds for avid birdwatchers and ornithologists. This denizen inhabits a very restricted range of the Chocó Region of Colombia and Ecuador.

Wandering around the humid forests of the Chocó, the cuckoo—also known as the Chocó Roadrunner—stalks armies of ants that march along the forest floor. Since the first recorded sighting of the cuckoo in Un Poco del Chocó, several serious birders have visited this reserve for a close view of this elusive bird. In November 2014, I finally spotted the cuckoo there and added it to my pocket list.

A Banded Ground Cuckoo spotted in Ecuador's Un Poco del Chocó Reserve. Credit: Manuel Sánchez

One of the most sought–after neotropical birds was assessed by Brazilian scientists in 2011. They placed it in the Thamnophilidae group—which in Greek means "bush lovers"—because almost all Thamnophilids inhabit the forest floor. Studies like these are generating new classifications for birds and shedding more light on the biodiversity of the Neotropics.

Line drawing by Manuel Sánchez.

Future research hopes to clarify whether the Wing-banded Antbirds living from eastern Nicaragua to northwest Colombia are a different species than those found from East Colombia to the Guianas, the Amazon of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, and the eastern Amazon of Brazil. Studies like these are generating new classifications and systematics of the biodiversity of the Neotropics.

Neotropical birds face several threats in the region. The exploitation of nonrenewable resources, unsustainable agriculture, overfishing, deforestation, invasive species, pollution and infrastructure development are considered the major causes for extinction and population decline.

But other types of human activities are destroying entire ecosystems, too. Illegal farming and the trafficking of drugs in Latin America have fragmented forests important to birds. The future is not promising, even for some species considered common in the Amazon basin. In 2011, a study published in Diversity and Distributions predicted that the habitat loss due to deforestation could be a threat to more than 90 species in the Amazon. Therefore, species considered common such as the Ruddy Pigeon or Black Caracara, are now both considered vulnerable to extinction in this publication, along with many more.

According to the IUCN Red List, the four neotropical countries with the most species of birds in the world (Colombia, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador) are also placed in the top five of countries with most birds in danger of extinction, with Brazil leading the group and Indonesia with them.

An Elegant Trogon. Credit: Dominic Sherony via Wikipedia.

Latin America's Neotropics, a unique and fragile region of the world, offers the chance to observe hundreds of different colorful birds—and some rare species, too.

To facilitate this kind of tourism, the region must invest in training local birdwatchers and creating birding clubs. Some reserves have been established that protect wildlife, but the promotion of sustainable activities in the Neotropics is essential to preserving the ecosystems. We have to start as soon as possible if we want to continue feeling proud of one of the most biodiverse regions in the world.

Manuel Sánchez is a field assistant in ornithology and a birdwatching guide with a Master's in science communication from Edinburgh University. He has traveled throughout South America guiding ornithologists and building support for birdwatching tourism. He has been involved with new registrations of avian distribution in Ecuador. His recordings of bird vocalizations can be found here. Follow him on Twitter @clandestinebird.