How Latin America prepared for the possibility of an Ebola outbreak

When Souleymane Bah arrived at a hospital in Cascavel, in the Brazilian state of Paraná, he never imagined that in a few hours he would be in every newspaper in the country. Showing symptoms of a fever, the Guinean quickly became the first suspected case of Ebola in Latin America and he generated an impressive operational lockdown.

After isolating the patient, authorities transferred him by helicopter to the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Disease in Rio de Janeiro, where he underwent rigorous testing. A few days later, Brazilian authorities ruled out the fact that Bah was infected with the Ebola virus, which eventually led to tranquility. But the case showed how the ghost of this disease, which by January 2015 had caused more than 8,000 deaths in West Africa, had spooked Latin Americans, changing some habits and shaking up prejudices.

Ebola is transmitted by direct contact with a patient or their fluids (vomit, blood, urine or stool). It has a relatively short incubation period, ranging from two to 21 days, and a high mortality rate, enhanced because so far there is no safe drug to treat it nor a vaccine to prevent it.

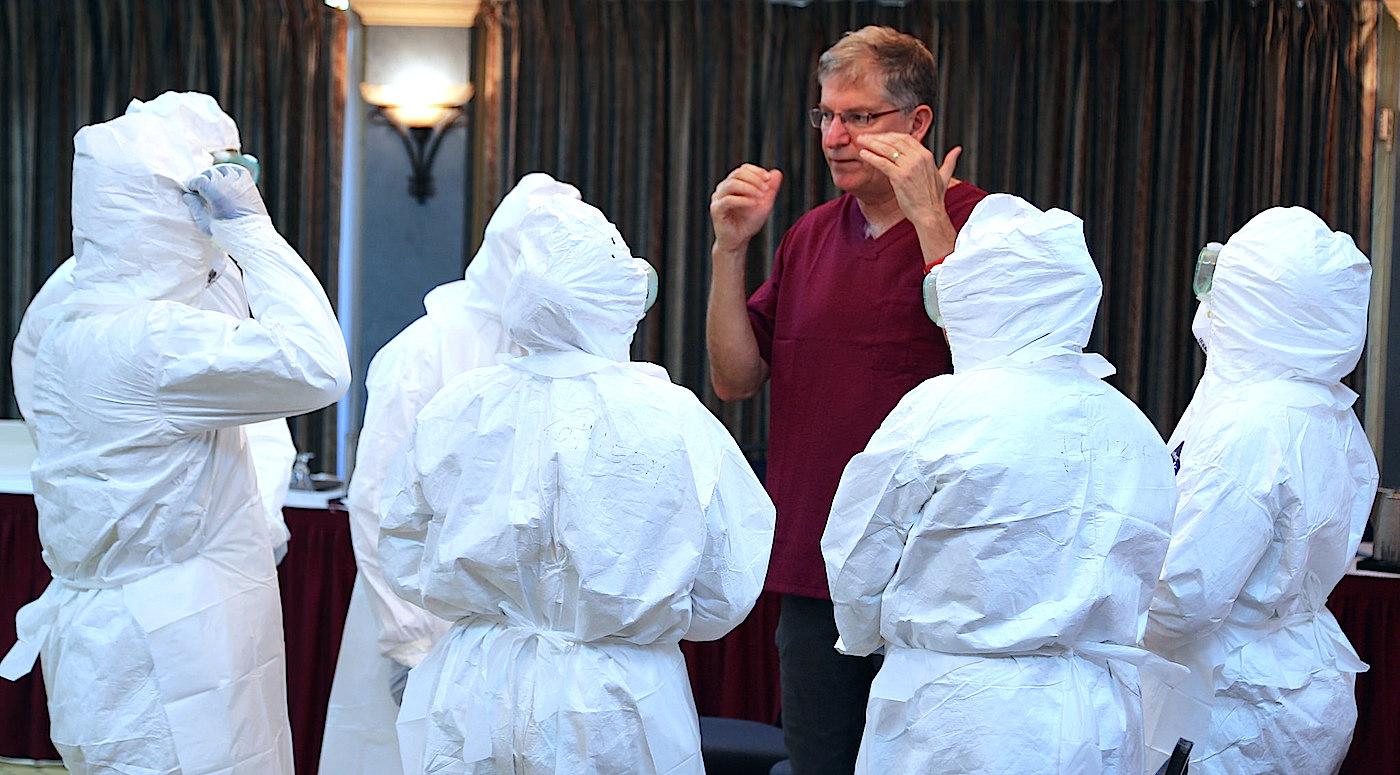

A PAHO training of Cuban doctors to contain possible cases. Credit: PAHO.

The world lives in fear of a disastrous pandemic that will strike humanity. Etched into our social consciousness are the millions of deaths caused by yellow fever, plague, the Spanish flu, and other massive epidemics. In the face of epidemics, the world is scared and on alert. As was the case with the H1N1 swine flu virus—which was declared a pandemic in 2009—Ebola has rekindled those fears in Latin America and the world.

The first cases of the current Ebola epidemic occurred in March 2014 in Guinea but experts say that the virus was circulating in the country as early as December 2013. A few days later, cases were confirmed in Liberia, a neighboring country. By the end of that month, Sierra Leone became the third country affected at which point the World Health Organization (WHO) admitted that the epidemic was "out of control." In July, Nigeria confirmed that it had the virus. Despite early efforts, cases multiplied, including many among health staff, like the Spanish nurse who became the first case outside of Africa.

The planet went on high alert. In Latin America, health authorities began work on emergency protocols and contingency plans to address possible cases. Although specialists considered the possibility of an outbreak on the continent distant, prevention and control plans were effectively used, as in the case of Souleymane Bah in Brazil.

A training course for Ebola patient management in St. John's in the Caribbean in December 2014. Credit: PAHO

To work with Latin American authorities, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) sent a series of experts to over 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. The aim was to improve the preparedness of countries to detect and respond to a potential case of Ebola. "True preparedness does not stem solely from contingency plans but needs to be firmly imbedded in robust national health systems, a trained health workforce, and a supportive network of regional and global partners capable of coordinating efforts and channeling sufficient resources to act timely,” the PAHO wrote in a January 2015 bulletin.

“Everyone has the ghost of a massive outbreak in their head”All this preparation, however, did not stop the fear, at least at the beginning of the epidemic, from becoming embedded in Latin Americans. So admits Omar Sued, an infectious disease expert and member of the Argentine Society of Infectious Diseases (SADI). "Everyone has the ghost of a massive outbreak in their head,” Sued told LatinAmericanScience.org.

Asked about the situation in the region in general and Argentina in particular regarding Ebola, Sued added that: "We are concerned as a country or as a system, but individually we do not have to generate concern yet, because while there are no active cases, there is no risk to the population."

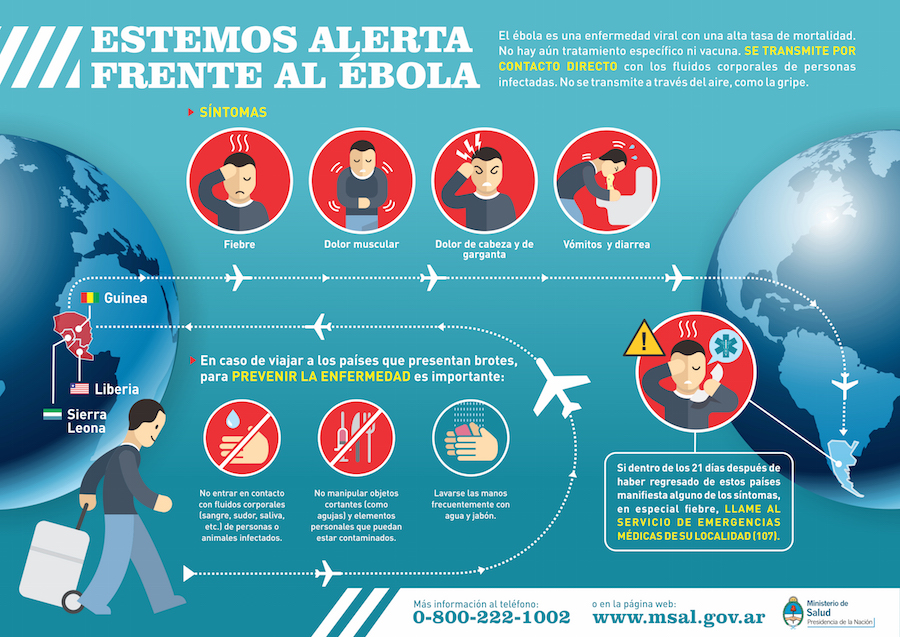

When the outbreak first erupted, the SADI published a bulletin which provided details about the disease, its mode of transmission, its symptoms, and how to prevent it. "If in the last month you have traveled or had contact with people who have traveled to areas of West Africa, and you present symptoms including flu, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, consult with your doctors," said the the document. The symptoms, the SADI added, appear two to 21 days after contracting the disease.

Presentation of emergency protocols in Chile. Credit: PAHO

Though it seems Latin America may be far from the epidemic’s reach, experts warn that it is difficult to predict outbreaks of this magnitude. Indeed, Sued says the spread of cases from Guinea to Liberia and other African countries is almost casual in its nature.

"Ebola has been in that part of Africa since ’74 and there had always been small outbreaks that were contained. Apparently poverty and lack of economic opportunities resulted in the deforestation of an entire country where there are lots of bats infected with the virus which went to four cities with a lot of migration, which generated an imbalance that is associated with the outbreak,” he said.

More than a year after the outbreak was declared, the only country in the Americas to have a recorded case of Ebola is the United States. But the tools with which authorities will face the possibility of infection are out and ready.

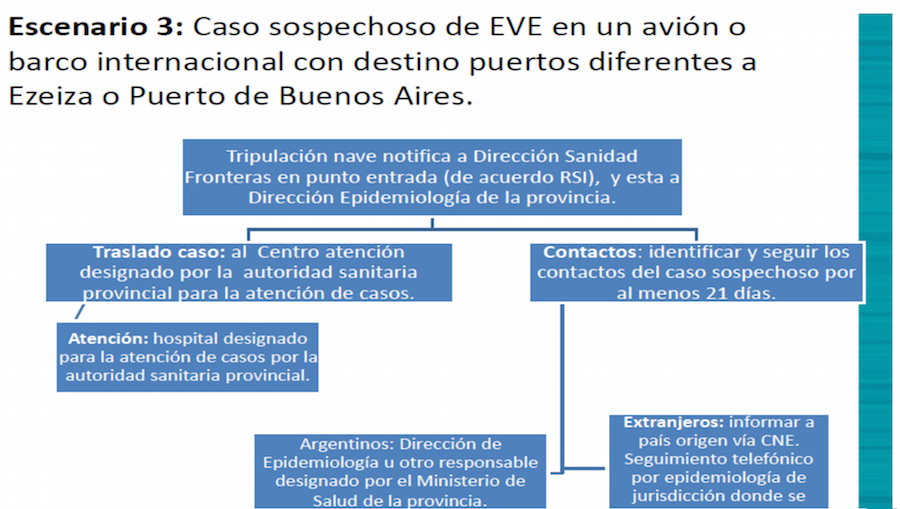

Over the last week of January 2015 in the city of Buenos Aires, two young women showed up at a hospital with fever and stomach problems. What could have been a routine visit ended with the activation of Ebola emergency protocols established by Argentina’s Ministry of Health for cases of Ebola. The women, ages 23 and 16, came from a mission trip in Nigeria, where they had been in contact with people from across the region. Although the tests came back negative, the alarm had been sounded and Argentina showed it was, at least in theory, prepared to contain the epidemic.

Ebola information supplied by the Argentine Ministry of Health.

In August 2014, when the epidemic showed no signs of weakening, the Argentine Ministry of Health issued a plan for potentially infected travelers arriving to the country. These people, highlights the document, "Will be isolated, tested and eventually transferred in compliance with protection measures to the Néstor Kirchner hospital of the town of Florencio Varela or the Juan P. Garrahan Hospital of Pediatrics, designated facilities for the handling of these cases." The INEI-ANLIS Carlos Malbrán national laboratory was named to analyze samples and confirm cases, if necessary.

Although the tests came back negative, the alarm had been sounded and Argentina showed it was, at least in theory, prepared to contain the epidemic."Our health system is on epidemiological alert which means that referral hospitals are already defined and key information for health teams spread, which is to say when to suspect a case, how to diagnose and treat it, how to prevent infections, how to notify authorities about the presence of a sickened person of this severity,” said Buenos Aires Health Minister Alejandro Collia.

The contingency plan against Ebola drew criticism, though. The union representing doctors in the province of Buenos Aires considered the public health infrastructure unable to cope with a hypothetical outbreak.

"In the province of Buenos Aires, the Ministry of Health took some steps, but our hospitals are not prepared for Ebola nor to address many less serious issues than an epidemic," said Márta Marquez, vice president of the Asociación Sindical de Profesionales de la Salud (Unionized Association of Health Professionals) of the province of Buenos Aires (CICOP).

Training by the PAHO on protective equipment and isolation. Credit: PAHO

In an interview with LatinAmericanScience.org, Márquez confirmed her criticism and said that in the health system "we have serious infrastructure problems, old hospital buildings… and an almost historic demand on our unions for our patients to have the right care."

In 2014, the union leadership rejected the fact that a Mar del Plata city hospital had been chosen as a site to contain Ebola. If we were to have a case of Ebola under the conditions we operate in, we’d be running away,” said Alejandro Loreti, a delegate of the CICOP, who said the hospital did not have "masks for communicable diseases and least of all [do we have the] elements to face Ebola."

Argentina's protocol for handling suspected cases of Ebola. Credit: Argenitina's Ministry of Health.

The African Ebola outbreak worldwide awakened the ghost of an epidemic of global reach, and feeding this fear were the horrific images that were coming from affected countries. Images of people dying on the floor and health workers insulated in protective suits piling up corpses quickly swept the world and warned of the seriousness of the situation. The idea of a pandemic popularized by the movie Contagion was now part of our innermost fears.

For some scientists, such as Maria Zambon, a virologist at Public Health England, this possibility is not pure science fiction, and in the short term can be very real. "During the last century we have had four major flu epidemics, in addition to AIDS and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome). Massive pandemics plague the world every century and it is inevitable that at least one will occur in the future," said Zambon.

"Massive pandemics plague the world every century and it is inevitable that at least one will occur in the future""Throughout history there have been major pandemics, mass epidemics that have killed millions," explained Omar Sued, the Argentine infectious disease expert. "Now there are mechanisms to contain the spread of this type of epidemic among countries. The WHO has an international regulation to prevent this transmission of infections... ensuring border health, limiting the export of some elements, disinfecting aircraft. All mechanisms to avoid a massive epidemic."

Sued doesn’t believe in a situation like the film Contagion. "I do not think there's an epidemic that can kill millions of people in one year, although, in fact, we do have them: the tuberculosis epidemic kills one million people and we have the obesity epidemic. But the emergence of a new agent, I do not see it," he said.

Whether you think like Zambón, or are more cautious like Sued, the threat of an epidemic is in our heads. And every so often, it resurfaces. Because, as suggested by the Irish writer George Bernard Shaw, "There is always danger for those who are afraid."

Diego Lanese is a science journalist living in Buenos Aires. He has written for the Argentine newspaper BAE, El Federal magazine, VBV magazine, and Mirada, among others. He is a science columnist for the radio program Aire Nativo (from Radio Ele in Lomas de Zamora). He is currently writing a book on the neglected diseases of Argentina. Follow him on Twitter at @diegolanese.

Edits and story layout by Aleszu Bajak.