Elephants and spearheads

in Sonora, Mexico

by Michelle María Early Capistrán

It's the end of the last Ice Age and the beginning of human settlement in the Americas. A group of hunters hide among creosote bushes and sagebrush, silent, waiting for their huge prey to show a hint of distraction or vulnerability. Armed with spears, they pounce on the giant: a gomphothere, a peculiar prehistoric relative of the elephant. Around 13,000 years later, the tips of their spears and the ashes left by their fires reveal new facets of the continent's deep past.

At the archaeological site El Fin del Mundo, in Sonora, Mexico, a group of archaeologists led by Dr. Guadalupe Sanchez has found Clovis spearheads associated with fossil remains of two gomphotheres. The Clovis points are characteristic of the oldest prehistoric tradition in the Americas.

It was believed that this species of prehistoric elephants had disappeared more than 20,000 years before the arrival of the first humans, but this discovery provides evidence that the gomphotheres coexisted with the first humans to walk the Americas. Sanchez and her colleagues published their results last July in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In El Fin del Mundo, the end of an era and the beginning of another can be seen among bones, rocks and strata. In this interview, Dr. Sanchez talks about the peopling of America and how the understanding of the distant past can help us tackle climate change.

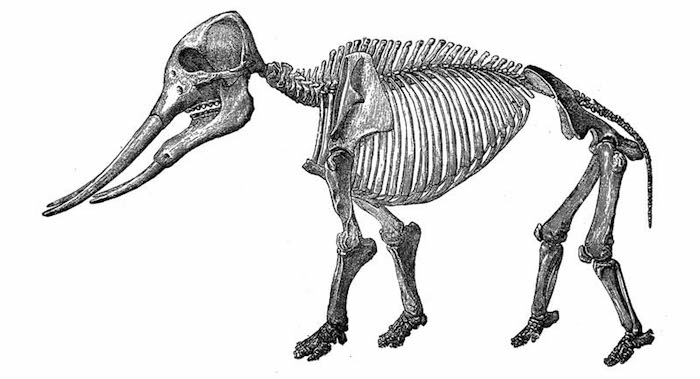

Cuvieronius sp.

Ever since I was in high school I wanted to study anthropology or archeology. In the end I decided on archeology, because I wanted to know about human processes. My interest in prehistory, especially the first settlers of the Americas, started because few people were working on the subject. On one occasion I was asked to write a short text about the prehistory of Sonora. We went to visit the sites that were already known, and easily found several Clovis points.  Sonora, Mexico

On that first trip we found four or five. It was then that I realized the potential there was in Sonora to study the first settlers of the Americas. Then, with the support of my professors at the University of Arizona, I began to study this topic. I never thought I would have so much evidence of the first inhabitants in Sonora, but when we began to look, we saw that there was a lot of material and that someone had to study it. So I started to study it.

Sonora, Mexico

On that first trip we found four or five. It was then that I realized the potential there was in Sonora to study the first settlers of the Americas. Then, with the support of my professors at the University of Arizona, I began to study this topic. I never thought I would have so much evidence of the first inhabitants in Sonora, but when we began to look, we saw that there was a lot of material and that someone had to study it. So I started to study it.

One of the main challenges of working in northern Mexico and Sonora is that it's far from central Mexico. In the INAH (Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History), almost all the members of the archeology department study Mesoamerica. They don't realize how different the techniques are to study the different sites. Many times students who come to assist in investigations only have experience in Mesoamerica. It's very difficult to make them see the little things that identify the sites—like a projectile point, for example—because a lot of times there's no architecture, no structural remains. In order to find the sites, we have to learn to see these things on the ground that seem insignificant. The other challenge is ensuring that the same authorities believe that this is of interest. There may be no pyramids, but it's very interesting to know who the first inhabitants who came to the Americas were.

What interests me most about archeology—although I am very interested in the first inhabitants—is learning about those of whom nothing is known, those whose history is not written and whom researchers have hardly studied. In Sonora that's one of the challenges. The most studied regions in the Americas are Mesoamerica and the Southwest U.S. This region of northern Mexico has hardly been studied. I want to reach these regions where you can find things that no one else has found. Furthermore, in this area of the Sonoran desert, preservation of remains is very good because there is little moisture. Since there is almost no rain, materials stay buried for long periods of time and there is little change after the abandonment of the site. I think that's very interesting because you can find a lot of intact evidence in the Sonoran Desert. Sometimes in the desert you can find things that seem almost as if they had been in a cave or in a more protected place. That's one of the things that has always attracted me. At El Fin del Mundo, we also find these fossils that, although they are not in very good condition, they are very old.

El Fin del Mundo is a site where Clovis points were found associated with the remains of gomphotheres. Gomphotheres were a species of mammoth. They weren't mammoths, but they were from the same family, they were a slightly smaller species of elephant that existed during the Pleistocene (2.5 million to 11,700 years ago). Two juvenile gomphotheres were found associated with Clovis points. So far we have about five Clovis points associated with these gomphotheres. This itself is a unique find because it is the first time gomphotheres have been found to be associated with Clovis points. What little research had been done by paleontologists who study Pleistocene fauna proposed that gomphotheres in this region had disappeared 35,000 years ago. For example, in places like Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles, all gomphothere dates hover around 35,000 years ago. So they thought that the first settlers who came to the Americas never saw these animals because they had already disappeared.

So far we have about five Clovis points associated with these gomphotheresBut at El Fin del Mundo, we found that Clovis points were associated with gomphotheres. It was very clear that the Clovis hunters were butchering the gomphotheres, or killing them and butchering them. They used these animals. I think it's something very interesting that you can see at El Fin del Mundo. The other thing we've found in the past two years (because the project has been going on for six or seven years) is carbon associated with the flakes, the projectile points and the gomphothere bones which are dated at 13.350 years B.P. This is one of the earliest Clovis dates. It's one of the things we need to investigate further, to see why they are such early dates. It is believed that humans migrated from north to south. In that case, why are the earliest dates in the southernmost Clovis site? It is a contribution that still can not be explained very well in the debate about the first inhabitants of the Americas.

Right now I have been working with soil scientists from the Institute of Geology at the UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico). I am also trained in macrobotanic pollen analysis. It's actually what interested me before fully entering prehistory, because I worked for several years at the pollen analysis laboratory at the University of Arizona. Right now I'm part of a project for Basic Research with CONACYT called "Human Adaptations and Climate Change." As part of this research, we'll study many issues related to paleoecology. In this case, when you're talking about archaeological sites, you need a soil scientist to explain processes like soil formation: whether or not the soil disappeared, if it was wet or not. Along with this you need to study pollen and other macrofossils that might be found. I think this project will be very interesting because we will go back to the other archaeological sites that I have researched where paleoecology hasn't been studied in detail.

I think this is fundamental: seeing how these climate changes led to desertificationWe are returning to these sites because there are at least two or three major climatic changes that affected the way human groups were living, including the Clovis culture. When the Clovis people had just arrived in this area of Sonora, the Pleistocene ended and the Sonoran Desert began. They had to adapt to these new conditions because they no longer had elephants, mammoths or gomphotheres in the area. I think this is fundamental: seeing how these climate changes led to desertification. Right now, with current climate change, desertification has increased in many regions. Seeing what happened in the past, from 13,000 years ago until now, is a way to apply paleoecology to today and understand what is happening with the climatic changes that humans are causing to the planet. I think that part is fundamental.

Michelle María Early Capistrán is a cultural anthropologist by training, but the currents of the North Pacific Ocean led her to marine biology. She received a graduate degree in Marine Sciences and Limnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and currently investigates human interactions with long-term marine ecosystems by integrating ethnographic fieldwork, archival research and statistical analysis. Follow her on Twitter at @earlycapistran.

Guadalupe Sanchez is a research associate at the Institute of Geology-ERNO UNAM. She obtained her degree at the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH), and her masters and doctorate at the School of Anthropology of the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. Over the past 20 years, her research has focused on Northern Mexico on several topics which include hunter-gatherers of the Pleistocene-Holocene, the early introduction of corn and agriculture, human adaptations, geoarchaeology, paleoethnobotany, and paleoecology. She is currently leading field research at the site El Fin del Mundo in Sonora. Her main interest is human adaptations and long-term climate changes in the Sonoran Desert. She has published extensively on these topics in English and Spanish.