Descending in latitude towards the Baja California peninsula, precipitation decreases and vegetation survives mainly on moisture from fog. This is the southern edge of the North American Mediterranean region, 250 km south of the US-Mexico border in the Mexican state of Baja California. Here the Mediterranean vegetation gives way to the desert to form a unique mix of flora landscapes, where the boojum trees meet the manzanita, the cardón cactus encounters the artemisias. Despite semiarid conditions, this is also where a modern agricultural region has been established.

For a long time, this area’s economic development was constrained by the limited availability of water. In the mid-1970s, after numerous wells were drilled, an accelerated process of change began as thousands of hectares of natural habitat were converted to farmland.

However, water availability decreased shortly after a decade of excessive extraction, due to groundwater depletion and saline water intrusion. Investors with more money have built new wells and even large aqueducts to bring water in from the mountains; others have abandoned their fields or converted them to urban areas. The government, meanwhile, has built desalination plants to alleviate water shortages.

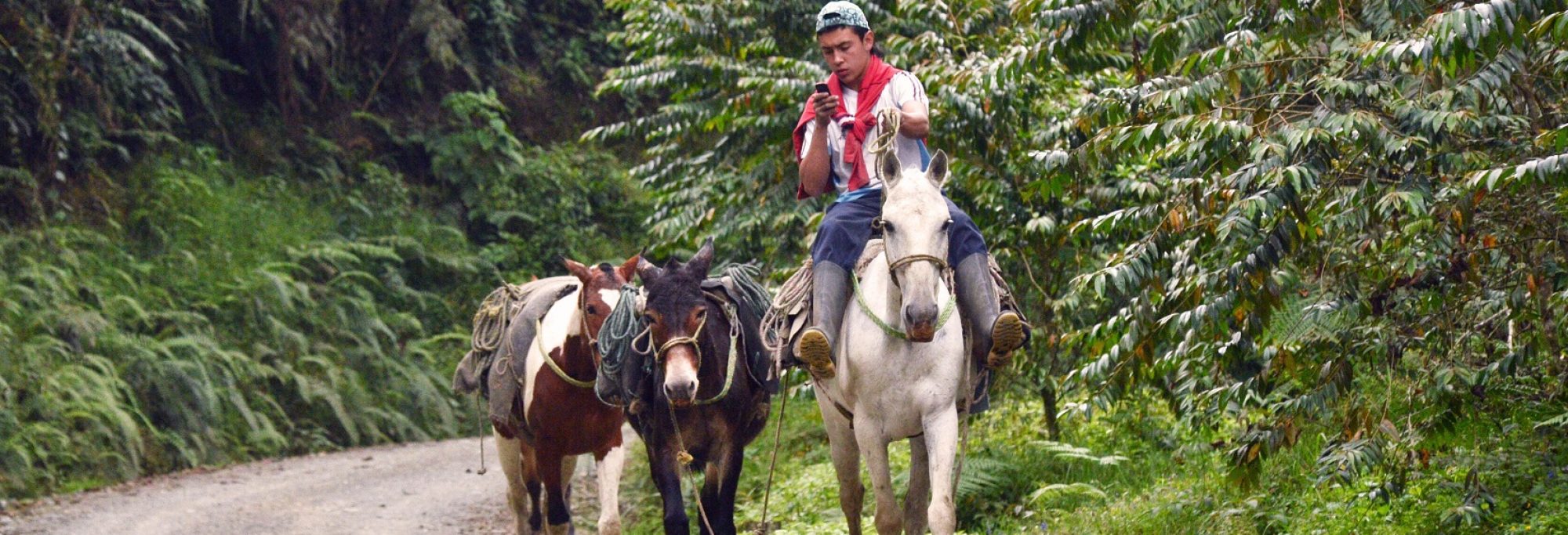

The establishment of this agricultural region has demanded labor and thousands of workers have been brought in from the southern states of Mexico. This has led to the gradual settlement of thousands of people and caused an exponential increase in population, from of a few hundred inhabitants to just over 50,000 today. This population growth poses challenges not only in terms of demands for services ― like water, drainage, paving, waste disposal, medical services and green areas, among others ― but also for the possibilities of harmonizing urban development with environmental protection.

Mediterranean regions of the Americas under threat

Regardless of political boundaries, Mediterranean regions face the same problems. Overgrazing, extensive agriculture, invasive species and urbanization, among other factors, have contributed to the degradation and fragmentation of native habitats.

In the world’s five Mediterranean regions, the summers are hot and dry while winters are mild and rainy. Rains also occur during the spring and fall. In these regions, located on the western side of continents between 30 ° and 40 ° north and south latitude, vegetation varies from forests to scublands, and aromatic species are common. They stand out for their biodiversity and unique flora, but are also subject to intense human pressure: both the Chilean and North American Mediterranean regions are densely populated.

The Mediterranean regions of North America and Chile are among the world’s 36 biodiversity hot spots, defined by the presence of more than 1,500 species of unique plants in an area that has lost at least 70 percent of its original habitat and is facing extreme threats. The North American region is characterized by prominent redwood forests, chaparral and scrub, and its Chilean counterpart by sclerophyllous forests formed by medium-sized trees with hard and thick leaves.

In Chile, eucalyptus and pine plantations have replaced up to 20,000 km2 of native vegetation and it is estimated that from 1970 to 1990, between 360 and 600 km2 of vegetation were burned each year, especially for Pinus radiata plantations (a fire-adapted North American conifer). These fires also affect the native vegetation. In the Mediterranean portion of the US, the intensity and frequency of fires have not only affected thousands of hectares of vegetation, but also residential areas. Some studies indicate that this is the result of human management in their attempt to suppress the fires.

Urbanization and population growth are other serious threats: both the Chilean Mediterranean region are densely populated. The former houses about 80 percent of the inhabitants of Chile, while the latter supports large cities like Los Angeles and San Diego in the US and Tijuana in Mexico.

Botanical Gardens as a tool for conservation

About one-third, or around 80,000, of the known species of vascular plants find shelter in botanical gardens, making them important for biodiversity conservation. They also function as dissemination points of knowledge about the natural environment, thus contributing to its appreciation.

In an attempt to help conserve the Mediterranean ecosystems of Baja California, San Quintin Botanical Garden, founded in 2016, represents the region’s coastal habitats, organizes interpretive tours to natural areas, and collaborates with researchers and individuals in order the promoting the value of native vegetation, advocating for its use in urban areas, and give quick responses to native habitat conservation threats. We hope these efforts will inspire action for ecosystem conservation elsewhere.

Jorge Simancas, is a conservationist who works in northwest Baja California and as a marine wildlife observer in the seas of the world. He is a cofounder of Jardín Botánico San Quintín. His scientific career has included studies of the micro, the macro, the plants and the animals. In his master thesis Jorge evaluated the quality of habitat during the non-breeding season of Black Brant geese in San Quintín Bay, Baja California. He has work in several national and state forest inventories, and was co-author of a population survey for nocturnal rodents in Reserva Natural Valle Tranquilo. Jorge is also co-author of “Mammals, Reserva Natural Valle Tranquilo and RN Punta Mazo.”